The text and photos are from

the 1952 Grand Island, New York Centennial Book. The dedication will follow.

Dedication

To those sturdy pioneer men and women, who braved the mighty Niagara seeking to establish the first semblance of a homeland on this majestic island and in spite of struggles unknown to us, succeeding in their attempt.

To their descendents and those who came from native as well as foreign shores, to continue the development of an island beautiful.

To those men and women who rallied to their country's call when it was necessary to establish the right and above all to those who gave their all to the cause of freedom.

Then to those who in the present and in the future will come to call our island homeland, this our Centennial book is humbly dedicated.

Forward

The story of beautiful, unique Grand Island is interesting and inspiring. As historians have been known throughout the ages to relate events as they deemed them to be worthy of record, it will also be found true of local history and events. More than that, it was necessary to determine how to fit into the time and space allotted the endless chain of events for a well rounded one hundred years.

Some, no doubt as they peruse the content of these pages, will recall with fondness, memories that are dear to them. Others will for the first time become acquainted with folklore and legend of Grand Island. Then will the purpose of the story be completed. Our pleasure was found in its preparation, yours in recalling to others throughout the ages.

Frances M. Yensan, Historian

The French missionaries, who came into Western New York in the seventeenth

century, found a peaceful Indian people. The missionaries called them the

Neutre Nation because they strove to maintain peace although surrounded by

warlike tribes. To the west of the Neutre Nation lived the Hurons; to the

east, the Senecas, members of the powerful Iroquois League, and to the south,

the Eries, enemies of the Iroquois. It was necessary for the warriors from

hostile tribes to use a land route, which passed through Neutre territory when

making raids on each other. The warring factions maintained a strict neutrality

in the villages and territory of the Neutres. This was not a happy situation for

the Neutres or for the warriors, impatient to come to grips with the enemy.

So the Senecas decided to wage war against the Neutres. When the bloody warfare finally came to an end in 1651, the Neutres nation ceased to exist and the small remnant of survivors were adopted by the victorious Senecas.

The Eries or Cat People, and then the Hurons fell under the Iroquois in their successful League. From 1655 on, the Iroquois League controlled most of New York State and what is now Grand Island. The Mohawks were given the guardianship of the eastern portion of the League territory, while the Senecas guarded the western entrance.

The Senecas called Grand Island Ga-we-not, meaning the great island. They used it as a hunting preserve but had no permanent villages here. The hunting parties came to the island to hunt deer, wolf and bear. The waters surrounding the island were filled with muskellunge, yellow pike, sturgeon, black bass and many other kinds of fish, furnishing the Indians with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of food. In the spring and fall, the shores of the island were thronged with geese, ducks and other game birds.

One temporary Indian village was located on what is now (Lot II) near the junction of Fix and East River roads. Another village was on the West River not far from the mouth of the Sixth creek (Six Mile Creek). Many Indian relics of the Neutre and Seneca nations, such as arrows, tomahawks, brass kettles and a Jesuit ring have been found on the island.

Check out this photo of an Indian " Trail Tree" found near the center of Grand Island in 1998, alive and well. A branch of a tree is fastened to the ground indicating the direction of a trail. The tree grows roots and becomes permanently attached to the ground maintaining the trail for hundreds of years. This "Trail Tree" points east.

There was an Indian burying ground at the head of the island near what is now Beaver Island State Park. An Indian burial mound was found in the center of the island. The Indian remains in this mound have been placed there after their temporary first burial. It was the custom of the Indians to hold a Festival of the Dead every eight to ten years. During this festival, the dead were taken out of the first or temporary burial place. Any flesh that still remained on the bones was removed, and the skeletal remains were wrapped in beaver skins and placed in the final burial mound.

The first authentic historical reference to Grand Island is found in Father Louis Hennepin's book Nouvelle Decouverte published in 1697. He describes the sailing of the Griffon up the Niagara River to its first anchorage between Grand Island and Squaw Island. He refers to "d'une grande Isle." The French called the island La Grande Isle.

During the early part of the eighteenth century, the island may have been visited by French traders, hunters, and missionaries, but it was off the beaten path. When supplies, soldiers and settlers from Quebec and Montreal, bound for the West, arrived at Fort Niagara, it was necessary to secure the services of Indian porters to carry the goods around the falls. The road was hardly more than a trail skirting the edge of the gorge. Above the falls, the bateaux would settle in the tranquil waters, the supplies tightly secured once more. After the settlers had retaken their places, the party would glide from the shore and up the west channel of the Niagara to Lake Erie. Madame de Cadillac, the wife of the governor of Detroit and the first white woman to come to this section, traversed this route when she journeyed from Quebec to Detroit to join her husband. She was carried from Fort Niagara to the re-embarkation point above the falls, sitting in a chair strapped to the back of an Indian.

During the French and Indian War, the French garrisons in the West sent aid to besieged Fort Niagara. The relief advanced as far as the north shore of Grand Island before beaching their canoes and bateaux in Burnt Ship Creek which separates Buckhorn Island from Grand Island. The main group hastened to Fort Niagara, but 150 men under the command of Roche-blanc were left to guard the French boats. The French were not able to relieve the Fort, and suffered severe losses in the attempt. The remnant of French forces that returned to Grand Island could not man all the boats. They decided to burn the surplus vessels so they would not fall into English hands. Then they returned to Detroit.

After the French and Indian Wars, Grand Island became part of the British domain. Sir William Johnson visited Grand Island, spending a night here in 1761. He encamped on the West Side of the island, near the mouth of Sixth Creek.

The British decided to use pack animals to carry supplies from Fort Niagara to Fort Schlosser above the falls. Many Indian porters lost their jobs and in retaliation attacked a caravan at Devil's Hole, massacring many people before help arrived from Fort Niagara.

Sir William Johnson called a council to meet at the fort. The Indians expressed regret for the massacre and to show their good faith gave all the islands in the Niagara River above the falls to Sir William Johnson. This treaty was signed at Fort Niagara August 6, 1764. Sir William Johnson immediately transferred the title of these islands to the King of England.

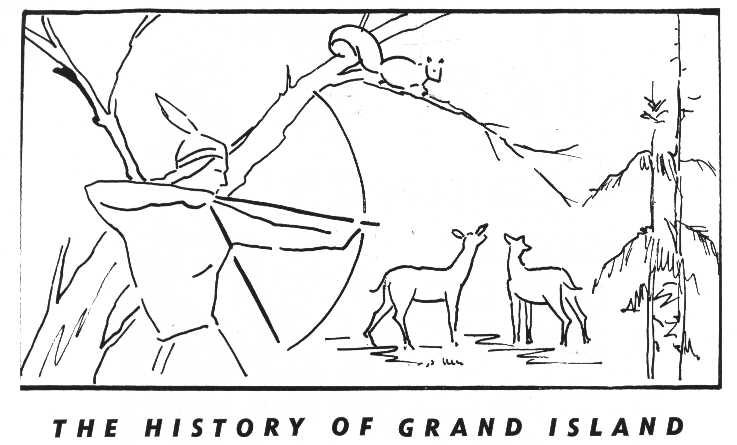

Although the Revolutionary War ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British continued to hold Fort Niagara until 1796. After the British were expelled from this area, the Iroquois claimed that the title to the islands in the river reverted to them. The State of New York, anxious to avoid antagonizing the Indians, recognized their claim. Representatives of the State met with the Indians in council at Buffalo Creek. There, on September l2, 1815, New York purchased Grand Island and other small islands in the Niagara River for one thousand dollars.

Ad in the 1952 Centennial Directory

Seneca Lawsuit Information Page

The title to Grand Island was not clear until the boundary survey of 1822. The boundary commission declared that the West branch of the Niagara River was the main channel of the river because it was deeper. The Treaty of Ghent had determined that the boundary between the United States and Canada was to be midstream of the Niagara River. Now that the midstream of the river was found to be the west channel, all the islands with the exception of Navy Island became a part of the United States.

Grand Island was the scene of the Porter-Smyth duel in 1812. The duel was probably fought in the neighborhood of Beaver Island Park because the dueling party was ferried to the island from Dayton's Tavern, below Black Rock. The cause of the ill feeling between the two men was in an article in the Buffalo Gazette, in which General Peter B. Porter accused Brigadier General Alexander Smyth, commanding officer of the United States Army in Buffalo, of cowardice. The weapons selected for the duel was pistols. Each contestant fired one shot but both shots went astray. Colonel Winder, who was acting as a second for General Smyth, arranged a truce. General Porter apologized. General Smyth retracted various uncomplimentary remarks about General Porter. The generals shook hands and the party was ferried back to the mainland.WHITE OAKS AND INTRUDERS

The next people to use the island did not have such a happy ending to their adventure. Americans have always wanted land of their own, nor were they afraid to go into the wilderness to obtain it. Daniel Boone led a group into what is now Kentucky. Other settlers pushed into western Georgia, northern Michigan, and finally across the Mississippi to the prairies. All the settlers had one thing in common: they were poor. If they could have purchased land in the more settled areas they would have done so. Eventually our government gave people free land in the West. There were two things wrong with the first settlers on Grand Island; they were poor, and they were fifty years ahead of the times.

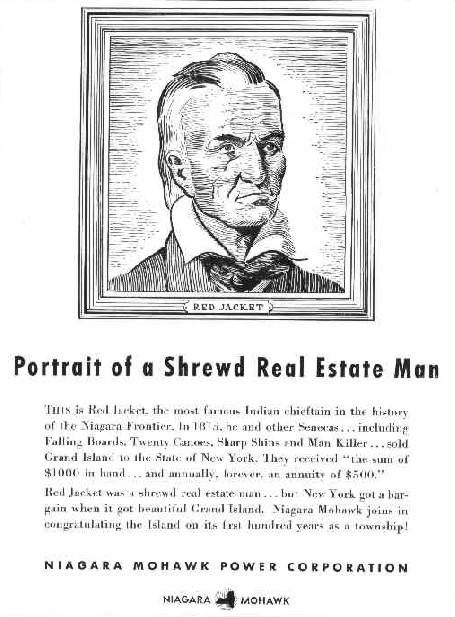

These hardy individuals who came to the island during the years 1817, 1818, and 1819 built log cabins. Then they cleared a small piece of land and put in a few crops. For ready cash, a scarce commodity on a frontier, they cut down white oak trees and made them into barrel staves. These staves were carried below the falls, then sent to Montreal. They finally wound up in the West Indies, where they were made into barrels to be used for molasses and rum. There were about seventy cabins on the island housing 150 people. Pendleton Clarke, who lived on the East River at what is now Lot 18, near Sour Spring Grove, was the leader of the squatters. Some people in Buffalo objected to the cutting of the white oaks. A doctor, Cyrenius Chapin, wrote to Governor Clinton asking that these settlers be removed. Doctor Chapin's description of the people on Grand Island was most unflattering. He called them "a collection of the refuse of society, constantly committing depredations on the island, by destroying, cutting and carrying off the valuable timber with which it abounds." The doctor asked the governor to stop the growth of the settlement before the "peace of this vicinity" would be shattered. Just how people on Grand Island could be such a nuisance to Buffalo is hard to understand. Buffalo at this period was a small collection of houses situated on Lake Erie and Buffalo Creek. The village extended northward about as far as Shelton Square today. There was a stretch of wilderness along the Niagara River to Black Rock. From the village of Black Rock to Tonawanda was more wilderness with an occasional farm. The Erie Canal did not reach this area until 1825. There was no regular ferry service between the island and the mainland. In spite of the natural factors that isolated the people on Grand Island, Doctor Chapin worried about the peace and quiet of the area. The doctor's protest received prompt attention in Albany. Governor Clinton consulted with his attorney general, Martin Van Buren, on the best steps to take to remove the homesteaders. The attorney general thought that the Legislature should pass a law ordering the settlers to leave the island. Accordingly, the governor sent a recommendation to the Legislature asking them to pass a law ordering the removal of the intruders from Grand Island. The act was passed in closing days of the Legislative session on April 13, 1819. The new law ordered the sheriff of Niagara county (Erie county was not created until 1821) to see that the settlers were removed and to use his own discretion as to the means of carrying out the terms of the law. In December 1819, Sheriff Cronk secured the services of the militia to aid him in driving out the squatters. He assembled his force consisting of two lieutenants, four corporals and twenty-four privates, at Main and Eagle streets in the village of Buffalo. The company marched out the River road to Seeley's tavern, where boatmen were hired to row them to the island. It was late afternoon when they reached the island, so the sheriff decided to pitch camp for the night and begin operations the next day. On December 9, they began their work of destruction. The owner of each cabin had the act of the Legislature read to him, then was told to gather up what- ever possessions he wished to keep. Finally the cabin was set afire. The people were allowed to go to Canada or to the mainland of the United States. It took the sheriff and his men five days to make the circuit of the island. The sheriff and the officers crossed the West river to Canada in search of amusement. They went on a spree and caused so much trouble there that warrants were issued for their arrest. But they managed to leave Canadian territory before the warrants could be served. Every family on the island moved to Canada except the Pendleton Clarkes. They moved to what is now Pendleton, New York. The cost to the state for this adventure was $578.99. Sheriff Cronk sent his bill to the governor on December 23, 1819 and he was paid in April, 1820. Some of the squatters returned to the island. When the sheriff tried to evict them a second time, one of their numbers pointed out the fact that they had been evicted once under the law and could not be driven off a second time. An editorial appeared in The Republican Press, July l 0, 1821, deploring the presence of squatters from Canada and demanding that some person of authority be appointed to guard the valuable timber from such people. Nothing was done. When the island was surveyed by the state in 1824, the land was divided into lots of not more than 200 acres. These were sold at public auction. Mr. Samuel Leggett of New York City, acting for Major Mordecai M. Noah, purchased 2,555 acres as a refuge for members of the Jewish race. The plan was to make Grand Island into a large and flourishing city. Major Noah ordered the cornerstone for his enterprise from the Cleveland quarries. He composed the inscription for it "Ararat, A City of Refuge for Jews, Founded by Mordecai Noah in the month Tizri 5586, September 1825 and in the 50th Year of American Independence."

This cornerstone was to be laid on Grand Island on September 15, 1825. However, when Major Noah and his assistant arrived in Buffalo from New York City, they discovered the inadequacy of the transportation to Grand Island, so decided to hold the ceremonies in St. Paul's Church in Buffalo. Many people, not knowing the change in plan, lined the bank of the Niagara River near Tonawanda hoping to see the ceremony.

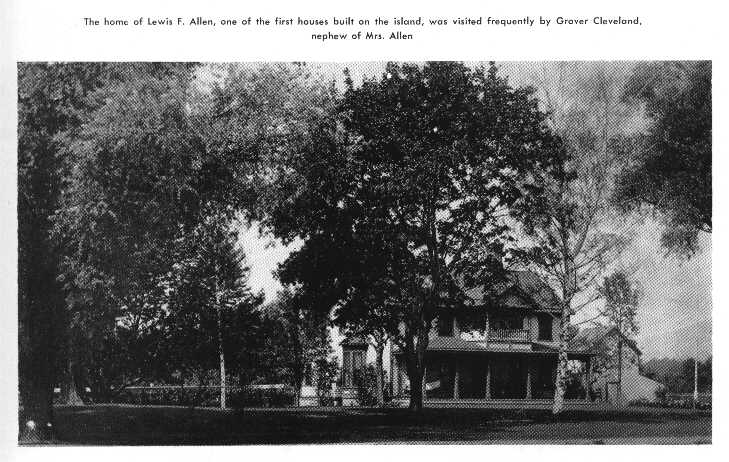

Major Noah returned to New York City and the proposed city did not materialize. The corner stone left at St. Paul's became the property of Peter B. Porter, who took it to his home in Black Rock. In 1834, General Porter gave the stone to Lewis F. Allen, who wanted it for the Whitehaven settlement. The stone was quite an attraction there. The river steamer operating between Buffalo and Schlosser stopped at Whitehaven so that the travelers could see the stone. After 1850, the stone came into the possession of Wallace Baxter, then to Charles H. Waite, who owned "Sheenwater." Finally in 1866, the cornerstone was placed in the Museum of the Buffalo Historical Society.WHITE OAKS AGAIN

The East Boston Company purchased about 16,000 acres of land on Grand Island for five dollars per acre in 1833. The Company planned to cut the white oaks and sell the timber to the shipyards in Boston and New York. The timber would be shipped via the Erie Canal.

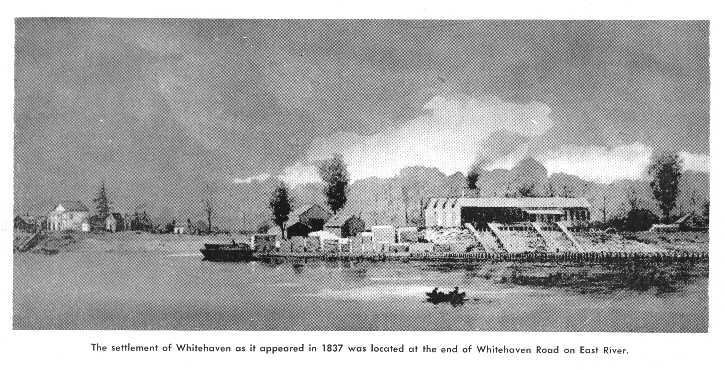

The Company cleared the land on the island opposite Tonawanda. A small "town" was laid out, including the beautiful home on the south portion of the cleared land now occupied by the Mesmer Supper Club. Bunkhouses for the Lumberjacks, a store, a building used as a school and a church, a dry dock, warehouses for ships' supplies and a long wharf were built. A gristmill and a sawmill were included in this settlement which was named Whitehaven in honor of Stephen White.

The sawmill at Whitehaven was said to be the largest steam saw in the world at that time. Six gangs of nine to ten men each were needed to keep the saw supplied with raw material. They used white oak logs from eighteen inches to five feet in diameter and from forty to seventy-five feet long. Each gang cut from five to six logs a day. Beside the woodcutters, the Company employed drivers for the oxen that pulled the logs to the river's edge, carpenters, sailors, black- smiths and storekeepers. Many French-Canadians as well as English, Scotch and Irish came to the island at this time. While Mr. Stephen White was in charge of White- haven, a group of the leading citizens in Buffalo planned to build an orphanage on the island. They planned to make this home a shelter for the boys who worked on the Erie Canal. Many of the boys, whose ages ranged from ten to fifteen, were employed as drivers for the canal boats. This was seasonal work and the winter usually found them without jobs and money. Mr. White offered to sell the sponsoring group one hundred acres of land at a very reasonable price. The Buffalo committee engaged the services of a Mrs. Orissa Heeley to act as housemother. The reason that the committee selected Grand Island for the proposed shelter was that once the boys were located on it, it would be very difficult for them to leave. Grand Islanders for the next century would have agreed with them. Evidently the committee was unable to raise the necessary funds, for there are no records of such as an orphanage actually functioning on the island. The Niagara Frontier throbbed with excitement during December, 1837 and January, 1838. William L. Mackenzie, the leader of rebels who attempted to overthrow the British rule in Canada, made Navy Island his headquarters. "General" Rensselaer Van Rensselaer joined Mackenzie on Navy Island. The people on the American side of the Niagara River sympathized with the rebels. The steamer Caroline was cut out of the ice in Buffalo harbor and readied for a trip to Black Rock, Whitehaven, Tonawanda and Schlosser. Her owner said that she carried passengers and freight "for the purpose of making money." But the British, observing her progress from the Canadian side of the river, believed that the object of the trip was to ferry supplies to Navy Island. The Caroline docked at Schlosser for the night. Around midnight, after the moon had set, a British force of seven boats under Captain Drew moved silently down the river. They boarded the Caroline, killed Amos Durfee, who was aboard her, set fire to the vessel and cut her moorings. The blazing ship was carried downstream toward the falls. The Americans were indignant, because the Caroline was in American waters and no state of war existed between the United States and Great Britain. Two companies of artillery with two field pieces were ordered to the barracks on Grand Island. Governor Marcy, General Scott and General Wool visited the militia camp there. The British had been firing eighteen and twenty-four pound shot at the island. Two schooners with British flags patrolled the West river. Some of the muskets and ammunition that the rebels were using belonged to the state of New York. This series of border clashes came to an end with the evacuation of Navy Island on the night of January 14, 1838. A large portion of Van Rensselaer's men landed on Grand Island. Colonel Ayer, the commandant of the barracks on Grand Island, took charge of the muskets and ammunition, which the rebels had sent to the island the previous night. The East Boston Company was interested in white oak timber exclusively. When the greater part of it had been cut, the company began to sell its holdings to individuals. Asa H. Ransom purchased 2,700 acres of land from which he secured about 100,000 cords of wood. Much of this wood was sold to the New York Central Railroad after being transported to Buffalo by boat. The island was still heavily wooded at this time. There were no roads, although a few hardy families such as the Hulings and Dinsmores lived inland from the river.

FARM LANDS

The farmers who purchased land in 1849 or a little later had to clear it before crops could be planted. This was a difficult job, involving the felling of trees, the pulling out of the stumps with the aid of oxen and then the burning of the brush. Sometimes large sections of the island were hidden under a pall of smoke.

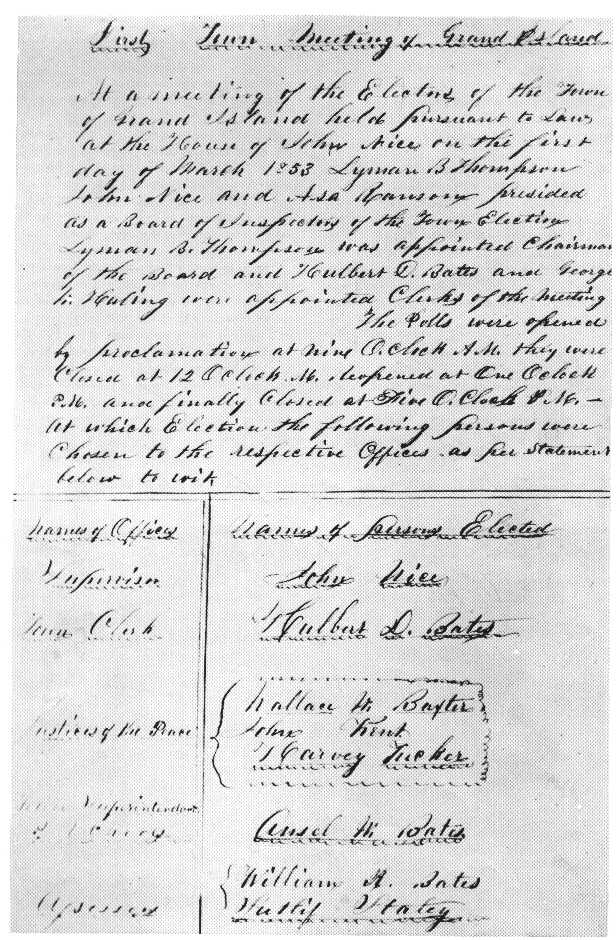

Once the land was cleared, it produced abundant crops of hay, wheat and grains. Mr. Lewis F. Allen reported that in the year 1860 he produced 350 tons of hay on his farm. The island soil was excellent for fruit trees. It is said that the first peach orchards in this area were on Grand Island. The Northern Spy apple was the variety found in many orchards as well as Greenings and Baldwins. Cherries, both sweet and sour, as well as Bartlett, Flemish Beauty and Seckle pears grew abundantly. The first farm houses were made of logs, with a door in the front center and another in the rear center. There were few windows. The next type of home erected was made of planks. There are some of these old plank houses still in use, although they have been covered with clapboards or shingles today. Good drinking water was a problem for the people away from the river. Most of the wells or springs south of Whitehaven Road are sulfur. The first farmers did not care for this water because it made very poor tea, and as most of the people were English, Irish or Scotch, this was a serious problem. Good drinking water was finally obtained by building cisterns that stored the rain water from the roof of the farm house. Grand Island, Buckhorn and Beaver Islands were made into the town of Grand Island in 1852. The first town election was held in the home of John Nice, who was elected supervisor. Town meetings were held in the spring. The elections for town officials were held in the various schoolhouses. The men voted by handing to the teller the ticket of the man of their choice. Later, the town hall was built. The main roads of the town were planned about this time. The north-south routes were the East River, Stony Point, Base Line and the West River Roads. For many years Base Line Road ended at Staley Road. It was necessary for travelers to use Staley for about a quarter of a mile to the west, then make a left turn through the Mesmer farm, then the Conboy farm and reach Love Road by way of the present Post Office driveway. Two immense willow trees stood on each side of the drive. The settlers called this "the gap." The east-west roads commemorate the names of some of the early settlers. Love Road was named for Volney Love, who lived on the west end of it near the West River. Staley Road took its name from the Staley family, who lived on the corner of West River and Staley Roads. Ransom Road calls to mind the Asa H. Ransom family. Whitehaven Road honored Stephen White. The Ira Bedell family, which came to the island from Vermont, gave its name to that road. Long and Huth Roads came into existence at a later date. The farmers on the island were better off than those in other sections of the country during the bad times of the seventies and the eighties. This may have been due to the diverse character of the farms and to the nearby markets. A typical farmer of this period sold hay, wheat, rye, oats, beef cattle, eggs, butter, apples and pears.

The Farmers Alliance movement was immediately successful on the island. The purpose of the Alliance was the social, educational, financial and political betterment of the farmer. Mr. Edward Huling was the first president, Henry Kaiser was secretary and purchasing agent, and George H. Alt was treasurer.

The Alliance members under the direction of William H. Conboy formed a stock company known as the Grand Island Creamery Company. It was capitalized at $25,000 and its chief purpose was to make dairy butter. Henry Stamler donated the land on which the building was erected, now the site of the home of the town clerk, Mrs. Elsie Stamler. John Grehlinger was made manager of the creamery, which handled about 5,000 pounds of milk daily.Although the cooperative movement was a success, farming on the island declined. Perhaps the reason for this decline was the fact that so many of the most energetic young men left the community for better economic opportunities in the city. Some of the reasons why the young people left were the constant struggles against the elements, the adverse policy of the national government and the difficulty of transportation to the 'mainland. It was a problem to keep people on farms, although in 1916, it was reported that the majority of farms on the island were occupied. From that time on, the island population declined, reaching its lowest point in the nineteen twenties.

A post office was established on Grand Island on October 9, 1877. The following list gives the names of the first postmasters:

W. CLEVELAND ALLEN October 9, 1877

FRANK JOHNSON February 3, 1880

CLARA BEDELL February 6, 1882

KATE D. BEDELL January 26, 1888

CHARLES W. LAISDELL April 27, 1888

WILLIAM S. LENNOX January 24, 1890

KATE D. BEDELL May 14, 1890

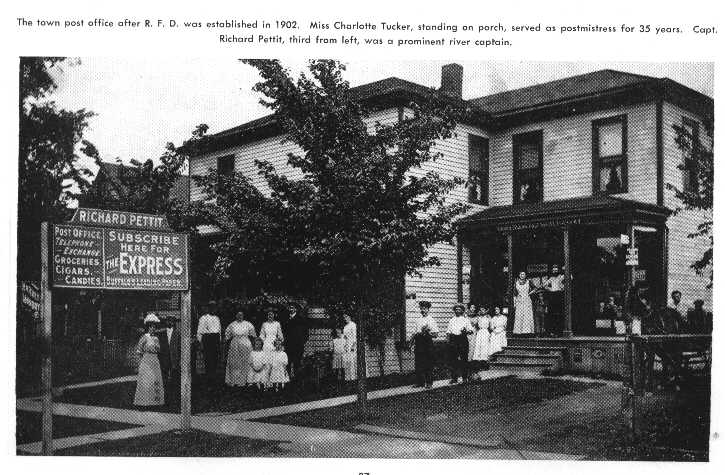

The town post office after R. F. D. was established in 1902. Miss Charlotte Tucker, standing on the porch, served as postmistress for 35 years. Capt. Richard Petitt, third from left, was a prominent river captain.

The creation of the Rural Free

Delivery service in 1902 was a real boon to farmers everywhere. Now they would

be able to receive and send mail every day instead of going to the post office

to pick it up. Miss Charlotte Tucker was the first postmistress under the new

law. She held that job until her death in 1937. Harry Tucker served as

postmaster from 1938 to 1944. The present postmaster, Edward T. Sheehan, was

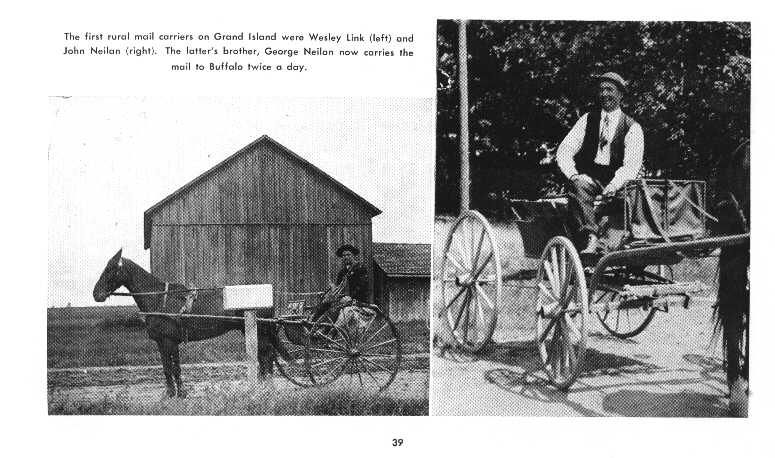

appointed in 1945. The first carriers were Wesley Link and John Neilan. They

were paid $600 per year and had to furnish their own horses. Since that time,

the late George Bell, Eugene Bucher and Harry Tucker have delivered the mail.

Robert Weatherbee took over Eugene Bucher's route when he retired in 195l.

The first rural mail carriers on Grand Island were Wesley Link (left), and John Neilan (right). The latter's brother, George Neilan, now carries the mail to Buffalo twice a day.

The farmers and their

families had to supply their own entertainment during many months of the year.

The last ferry left the mainland at six o'clock in the evening. The churches

provided much of the social life, as did such organizations as the Maccabees

and the Farmer's Alliance. The Congregational Church was the social center of

the island. There were Christmas festivities, a strawberry social in the spring

and a peach festival in the fall. St. Stephen's Church had a yearly picnic,

usually on the Fourth of July. Throughout the year there were card parties at

the church.

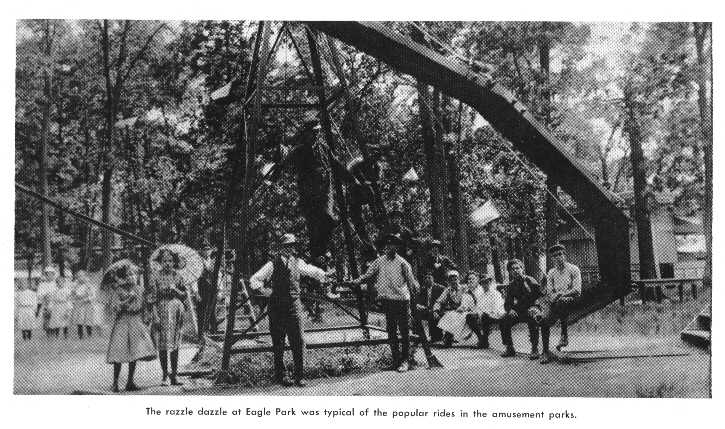

THE ISLAND AS A PLAYSPOT

The setting of Grand Island is one of great natural beauty, surrounded by the Niagara River, which is divided into the East and West channels at the head of the island. To the south from this point, the spark- ling expanse of river is broken by Strawberry Island and Motor Boat Island. The buildings of downtown Buffalo make an effective backdrop. The river is very shallow at the south end of the island and from the sandy beach, it is possible to walk into the stream a half mile toward the Canadian shore before it deepens abruptly. The west branch is wide and swift, and the Canadian shores offer a pleasant vista of woodland and cultivated areas. The northwest side of the island is cut off from Buckhorn Island by Burnt Ship Creek and from Navy Island by the river itself.

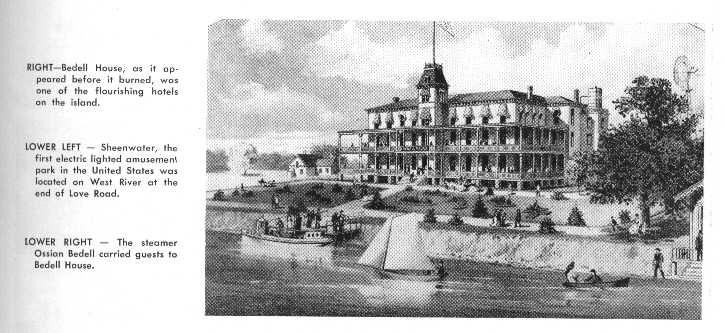

As the metropolitan areas of Buffalo, Niagara Falls and Tonawanda expanded, the sylvan quietude of the island became very attractive to city dwellers. Lewis F. Allen, who owned a large farm at the head of the island, decided to build a summer resort on the south west side which he called Falconwood. He gave this name to the place because of the number of hawks and eagles who made the large trees near the river bank their home. The first guests arrived at Falconwood on the steamer George O. Vail on Saturday afternoon, June 19, 1859. Falconwood later became a popular resort, open to the public. The steamers Cygnet and Arrow transported the vacation seekers the first year. During the first part of the Civil War, the following steamers made the trip from Buffalo to Falconwood: the Falcon and the Clifton in 1860, the Niagara in 1862 and the River Queen and Fanny White in 1863. By June 1865, Falconwood was closed to the public because it had become the property of the Falconwood House Company. This group was called The Falconwood Club and they became the owners of the steamer Falcon as well as the wharf one hundred ten feet in length; a hotel building sixty by forty feet in area, with a veranda twelve feet wide extending its full length; a saloon, a ballroom twenty-four by twenty feet in area separated from the hotel and situated about forty feet distant. In addition there was a bowling alley, assembly hall and two log houses. There Falconwood continued to flourish as one of the most popular of the island clubs of the last quarter of the 19th century. A group of Buffalo men, who called themselves the "Jolly Reefers," enjoyed the fishing off the head of the island around Beaver Island. A member of this group, later to be President of the United States, was Grover Cleveland. Cleveland knew Grand Island well because of his many visits to the summer home of his uncle, Lewis F. Allen.

THE LONG STRUGGLE FOR THE BRIDGES

The first time that a bridge was proposed for Grand Island was in 1819. In an Albany newspaper called the Argus, there appeared an article signed by "Pro- jector" demanding that a city of Erie be located on Grand Island and connected to the mainland by a bridge. Nothing came of this ambitious plan.

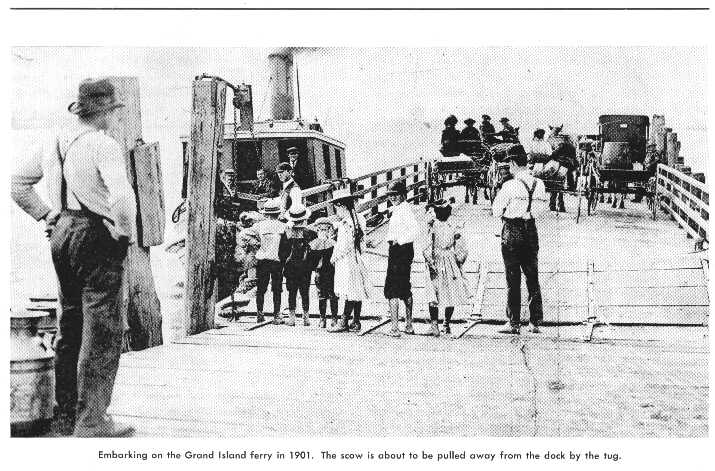

William Williams was given the franchise to operate a ferry from the south side of Tonawanda Creek to Grand Island in April, 1825. The State of New York gave a similar privilege to James Sweeney to operate a ferry from the north side of the creek to the island. About 1851, Jacob Schaeffer ran a ferry on the East River near the present south bridge. This was a very small ferry, having room for one team of horses or oxen. This little ferry was steam-driven, using wood for fuel. The ferry that Jacob Hensler operated between White Haven and Tonawanda was powered by horses on a treadmill. The establishment of ferry service from Bedell House to the foot of Sheridan Drive in the town of Tonawanda in 1874 saved the islanders many miles of mud road. When Lewis F. Allen decided to sell his extensive holdings on the island in 1887, he pointed out that Niagara Street was paved to within two miles of the ferry. The two ferries - the upper ferry leaving from Ferry and East River Roads for the foot of Sheridan Drive and the lower ferry, leaving from East River Road just south of White Haven for Tonawanda were the only means of year-round transportation to the mainland. They were expensive to use. In the 1930's, the passenger carfare was fifty cents for a round trip plus twenty cents for each passenger. A team of horses pulling a load of hay was one dollar. Heavier trucks cost more. The last ferry, for many months of the year, left the mainland at six o'clock in the evening. Sometimes because of ice or storms, the ferry was unable to operate for a day or two. The people of Grand Island really needed a bridge and longed for the day when they would have easy access to Buffalo and Tonawanda. At the short session of Congress in 1894, a bill was introduced to permit the building of a bridge. Mr. Peter DeGlopper, the supervisor at that time, believed that favorable action would be taken on the bill and went to Washington in January, 1895, to urge its passage. But the bill was sent to the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce and never released. The next year Mr. DeGlopper tried again. Ossian Bedell, William H. Wende and John Nice journeyed to Washington with him in an attempt to arouse enthusiasm for a new bill. But no definite action was taken by Congress. In February, 1898, everyone believed that the bridge was a certainty. The members of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce came to Grand Island to investigate the need for a bridge. There had been much discussion as to the type of bridge to be erected. Some marine men claimed that the proposed bridge had to be high enough for Lake Freighters to pass beneath it. But Major Symons, the federal engineer in charge of this district, denied that the Niagara River was a through route of commerce, in the same class as the Detroit River or St. Mary's River. He believed that the Niagara was part of the harbor extending from Buffalo to Tonawanda. Grand Island made great preparation to entertain the visiting Congressmen. The town board appointed the following committee to make the arrangements for the entertainment of the visitors: William K. Conboy, Ossian Bedell, John L. Nice, Horace Wende and Edward Huling. The board decided to meet the committee at the starting point of their trip in Buffalo. Dr. Arthur Bradbury, a member of the board, suggested that the supervisor, William Conboy, appoint a committee of eleven islanders, one from each of the school districts, to greet the Congressmen upon their arrival on Grand Island. The eleven members of the committee were John M. Huling, Charles Long, John Long, Jr., John Van Son, John V. Bedell, Fred Grehlinger, James Forsythe, Henry W. Long, Adam Kaiser, William Dinsmore and John Grehlinger. The entertainment committee, with Edward Huling as president and John L. Nice as secretary, asked Ossian Bedell, owner of the Bedell House, to open it for a banquet. Four hundred and fifty-four dinners were served there on Saturday, February 5, 1898. The expenses listed in the town records were: Flowers -$25.00The town committee had entertained so well that they exceeded their budget by $198.00.

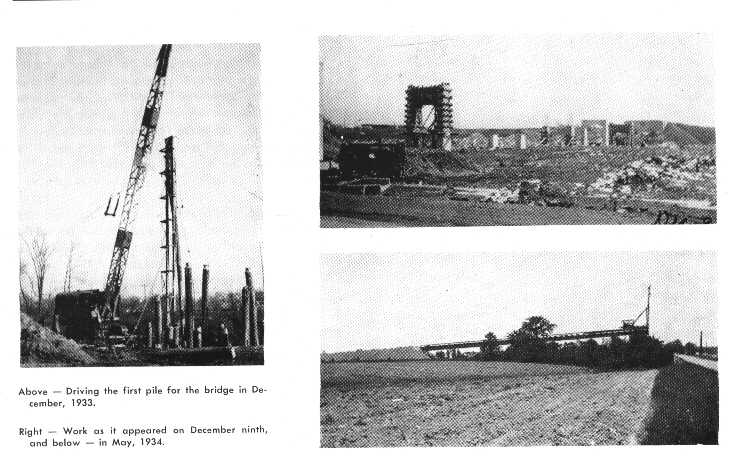

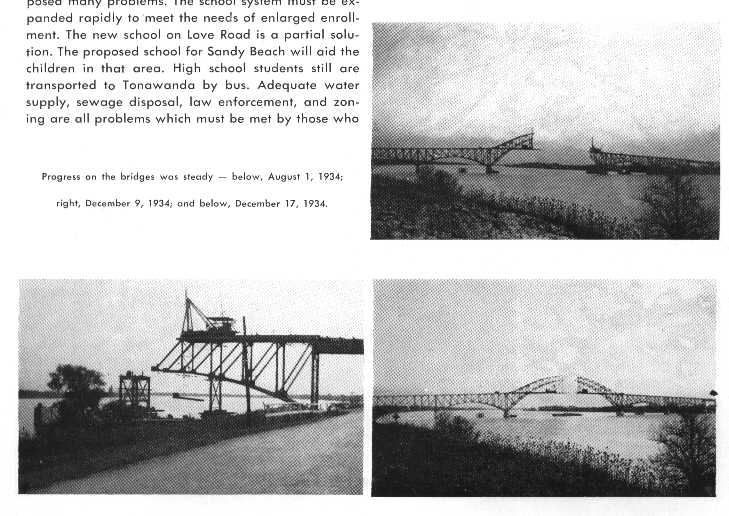

The bridge bill did become a law. But certain speculators who had secured the charter did not begin operations within the time limit. A new bill introduced by Mr. De Alva Alexander amended the original bridge bill. This amendment provided that the actual construction of the bridge must be commenced within one year (1902) and completed by June 30, 1904. But the bridge was not built. In the meantime the Town directed the supervisor, William Conboy, to ask the Board of Supervisors to appoint a committee to be known as the Grand Island Bridge Commission to supervise the building of a bridge to the island. But Erie County would not build the bridge. Two more attempts to secure a bridge occurred in 1904, when John V. Bedell was supervisor, and in 1907. The islanders tried to have the State of New York build the bridge. But nothing happened. The people must have been discouraged, because no more legislation for a bridge occurred until 1923. They had been refused a bridge by the federal, the state and the county governments. The American Niagara Railroad Corporation secured the right to build bridges across the Niagara from the United States to Canada from Congress in 1923. One of the proposed bridges was to be erected from the Town of Tonawanda to Grand Island; a second bridge from Grand Island to Brideburg, in the vicinity of Frenchmen's Creek, Ontario, Canada. Henry W. Long, the supervisor, Franklin Sidway and John Schutt, Jr., whom the Town Board had sent to Washington on behalf of the bill, returned jubilant over its passage. At the same time the New York Central Railroad purchased a strip of land about a half-mile wide and running from river to river on the south side of Staley Road. The Central planned to make this area the main terminal for its line in the Buffalo area, The Standard Oil Company secured a large tract of land on the south side of Love Road from East River to Base Line Road. Many oil storage tanks were erected. The company built a large dock to accommodate the tankers that were to bring the oil. But once more the bridge plan failed. Then the Niagara Frontier Planning Board was created by the State Legislature in 1925. Under the chairmanship of Chauncey J. Hamlin a survey was made recommending the building of a bridge to Grand Island. Mr. Hamlin interested State Senator Charles A. Freiberg and his secretary, Assemblyman Swartz, in the project. In l928 the Buffalo and Niagara Port Authority, which Senator Freiberg had helped to create, recommended the building of bridges to Grand Island. This recommendation was bitterly opposed by the Buffalo Chamber of Commerce, the late Mayor Schwab and Samuel Abotsford. Their opposition was powerful enough to influence Governor Alfred E. Smith to veto a bill carrying out the ideas of the Port Authority. Another bill was passed by the State Legislature giving a private company the right to build a bridge to Grand Island. Many islanders opposed this bill because they believed that a bridge should be free after it was paid for. They did not want a bridge company such as the Peace Bridge group to be collecting bridge tolls forever. William H. Conboy was one of the groups who spoke against the bill in Albany. Governor Smith vetoed it.

This website is sponsored by

GIECOM.NET